Winners and losers of housing policies: The stamp duty in focus

- stanimilcheva

- Jun 28, 2024

- 5 min read

In England, the Conservative Party's first point of call, when it comes to quick fixes on the housing market, is to use their favourite policy - changes to a property transaction tax, i.e. the stamp duty.

But what is the stamp duty?

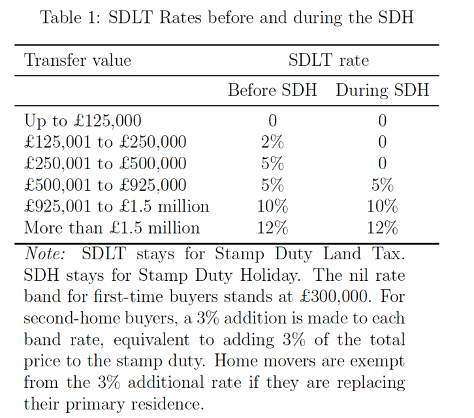

Stamp duty is a transaction tax on buying property and is fully paid by the buyer. It is a percentage of the house price. It can range from 0% and go all the way up to 17% (as of the date of this blog). It differentiates between first time buyers (people who never ever had a home) and home owners who are not first time buyers. It also differentaites between people who buy a home to live in or as a second (third, etc.) home. The latter pay 3% surcharge. The tax rate also increases as property prices increase in a tier system. This slice or tiered structure was introduced by the conservative-liberal coalition in 2014. Before that we had a slab system where the percentage of stamp duty tax was paid on the entire price.

The stamp duty tax makes a significant revenue for the government, bringing in £8.4 bn in 2019-20. This is more than double than what it used to bring in 2008-09.

Stamp duty holidays are not new and have been used to boost the housing market on various occasions. Previously, under the old, slab system, stamp duty holiday was introduced in 2008. The last time a stamp duty holiday was applied was during Covid. It was introduced on 8th July 2020 for an initial period until 31 March 2021. Subsequently, England, Wales, and Northern Ireland decided to extend the SDH until 30th June 2021. After 30th June 2021, SDLT was not paid for properties below £250,000 until the end of September 2021. A return to its original rates was announced for the 1st of October 2021.

The stamp duty holiday was associated with a temporary increase in the nil rate band for residential housing sales as part of a job-creation package during a statement to the House of Commons on the state of the economy amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Why was the stamp duty holiday introduced in 2020?

The objective was to stimulate housing market activity and boost the economy by driving demand for housing-related goods and services. According to the Treasury, it would achieve this by:

(i) Immediately lowering purchase costs;

(ii) By intentionally restricting the stamp duty holiday to a specific period, the policy aims to incentivise buyers to shift their plans forward to enjoy the benefits;

(iii) Freeing up money for buyers to spend on housing-related goods and services.

The question we ask in our research paper is: have the objectives of the stamp duty holiday policy been achieved?

Did the market revive?

To begin with, one the the implicit objectives was that the houshing market gets revived during Covid, as it has been substantially hit. And indeed, the market not only came back stronger due to Covid, it also was additionally heated by the stamp duty holiday. We see that monthly listings increased by 60% and transactions by 53%. This is subsantial and the policy has been highly effective in boosting buying and sellig of properties and making estate agents and other service providers in the sector, like mortgage brokers, solicitors, etc., happy.

Were the purchase costs lowered?

Quite the opposite effect was achieved. Perhaps the most significant and negative effect of this policy is that it made housing less affordable. The worst affected were the first time buyers who had nothing to sell. The sellers of housing that did not buy anything took most advantage of the stamp duty savings. One would expect that if a household buys a house of £300,000, it would have paying 2% of £125,000 and another 5% of 50,000. This amounts to £5,000. So, all else equal, the saving should have been 1.7%. I guess the government anticipated that this meant effectively this to be the same as a house price reduction, but instead, we document, that while market participants could have saved up to 1.7% of a £300,000 property, the prices did not stay the say. On average, the price increased between 1.9% and 2.5%. So, it more than offset the savings from the stamp duty holiday. A double whammy effect, is that while prices increased, buyers did not take advantage of the 1.7% savings from not paying stamp duty on the £300,000 property. Instead, the sellers were in a better negotiating position, and hence, they were able to bargain better and achieve close to their asking prices, which increased during the stamp duty holiday period. So, a seller would indeed be better off if stamp duty is decreased. In our examples, it would cash out the 1.7% savings and also expect an additional 1.9% to 2.5% increase in their house price on average. However, those sellers, unless offloading investment properties, would also need somewhere to live, so it might turn out to be a zero sum game, unless they are downsizing.

Who are the losers?

The biggest losers are first-time buyers or young households looking to buy a larger property.

Who are the winners of this policy?

Of course there are not only losers, but also winners. The policy favours elderly people who are looking to downsize, sellers who are looking to sell and move abroad, people with more than one property, who are looking for offload some of their assets. In addition, as mentioned above, mortgage brokers, estate agents, solicitors, valuers, etc. had a substanial boost in their work.

Were buyers incentivised to shift their plans forward to enjoy the benefits?

On the second point, aiming to incentivise buyers to shift their plans forward to enjoy the benefits, we do find that buyers and sellers changed their behaviour and indeed shifted their buying/selling decision to fit into the stamp duty holiday period, which initially was about 6 months. As transactions take on average 5.7 months to 7.4 months, there is a large degree of urgency to complete as quickly as possible before the tax break finishes. Due to this urgency, we find that, it is the sellers who are able to pressurise buyers rather than visa versa. The closer the transaction is to the deadline, the smaller the spread between the asking and the offer price. This means, buyers meet sellers not in the middle but very close to sellers' asking prices. Hence transaction prices and asking prices converge the closer we get to the end of the stamp duty holiday.

Was money freed up for buyers to spend on housing-related goods and services?

No! Buyers had less money, not more. As commented above, the people who benefitted the most, would most likely be wealthier anyways, and hence the marginal consumption by such households would not be substantial. Hence, the effect on the overall economy would not be noticeable. However, as mentioned above, a small group of businesses benefitted.

Finally, why have politicians once again suggested stamp duty reductions?

It is a popular policy as tax related policies often achieve immediate and large in scale effects. It is important that researchers like us evaluate the policy impact by conducting robust estimations. It is important that the media also reflects research like this one to shine a light on the effects of such policies and show that there are two sides of the coin.

Clearly, such policies do not favour less wealthy households and households who still do not own a property. They also do not really lead to innovation or efficiency or an increase in productivity. It redistributes the money from poorer to wealthier.

---Stanimira Milcheva is the author of this article and is a professor in real estate finance at UCL.

Find out more about this research on SSRN. ---

Recent Posts

See AllThe announcement that Hitachi will halt the nuclear mega project Wylfa plant in Wales came last week. Hitachi’s involvement in the power...

Comments